A Baptism of Fire and Rice

POSTED ON 01/12/2008Imagine you know next to nothing about wine and you’re told you’re going to taste 280 wines with the country’s experts. You might have an inkling of how weak my knees went as I was I thrown in at the deep end to taste 280 different sakes alongside 15 Japanese master sake brewers at the first International Sake Challenge in Tokyo. Ostensibly I was there as a judge in a Japanese wine competition, but along with the other international wine judges, I was roped in for the sake bungee jump as well. It was a baptism of fire and rice that was to kick off a blossoming affair with one of the world’s great traditional drinks.

Fire and rice

Fire and rice

Until that week, I had, like many, I suspect, been agnostic about sake, and when I kicked off my shoes in a traditional sake bar in Tokyo’s Roppongi district, my lack of enthusiasm wasn’t helped by a menu that included blowfish ovaries and the warty, salted and dried sea cucumber, whose gloopy, yellowy-green entrails tasted as unappetising as they looked. Enter John Gauntner, one of the world’s authorities, who illuminated the finer points of a drink I had tried once or twice previously but without any great enthusiasm. I learned that with its history, culture and multiplicity of styles, sake can be as complex in its own way as wine.

The more I learnt and, more to the point, tasted, the more I found sake growing on me. The special subtleties of sake were further illuminated when I visited the Matsumoto brewery in Kyoto. As I tried to describe the taste, the owner, Yasuhiro Matsumoto, cut me short and said it’s not how long it lingers but how ethereal it is that counts. After bowing profusely, he explained the secrets of the sake-manufacturing process: how pure water is essential for quality sake, how different rice varieties contribute to its character and how the ‘polishing’ of each rice grain by removing the outer fat and protein and retaining the inner core of starch is an essential part of sake’s quality. The most important differentiating factor of all though, he said, is the philosophy, ideology and skill of the brewer and his attention to detail.

Once a staple of the Japanese table, the consumption of sake, rather like table wine in Europe, has been in decline in Japan for two decades. The reasons are various but according to Kenji Ichishima, whose Niigata brewery I visited, sake today has dropped from a quarter of the total beverage market in 1975 to six per cent. The good news is though that outside Japan, it’s growing at over 10 per cent a year, mostly in the higher grade categories. ‘Young people in Japan have grown up in a Coca-Cola culture and don’t drink sake much’, says Kenji. ‘It’s what their parents drink. Premium sake is not cheap so if they drink sake at all, they mostly go for the hangover-inducing stuff. When we offer our premium sake at tastings, consumers really like the taste and overseas customers don’t have the prejudices young Japanese people have’.

As evidence of the decline of sake in Japan, the Matsumoto family is one of the very few to survive as sake brewers in Kyoto. When the family company was established in 1791 in Kyoto, there were 300 sake breweries in the city but by 2007, only three of the original breweries, including Matsumoto, survived. This mirrors Japan as a whole where the industry was also hit 20 years ago by the tax agency’s decision to stop issuing new brewing licences as existing master brewers retired without successors. There were an estimated 3,500 breweries in sake’s heyday of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Today there are less than half that number.

One country’s decline is another’s opportunity. Burgeoning sake exports are a consequence of the belated realisation by Japan’s sake breweries that survival of the fittest depends on capturing new markets. Although responsible for a small family operation, Kenji Ichishima himself is typical of the dynamic young breed of sake brewery owners. He speaks good English and travels the world, particularly the US, where Japan’s total sake imports of 11.3 million litres are ten times that of the UK. Roughly a third of Japan’s exports go to the US, followed by Taiwan, Hong Kong and, more recently, China, where shipments doubled to 4.3 million litres kilolitres in the four year period to 2006. The UK’s consumption is still small but sales have more than doubled in the past two years and are now worth over £2m per annum.

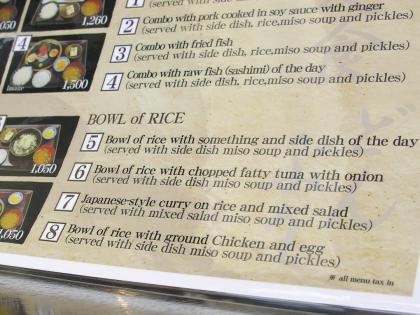

A little something with your rice, sir?

A little something with your rice, sir?

The reasons for sake’s growing popularity in the US and Europe extend beyond the simple equation of declining demand in Japan and a shift from a traditional fish and rice diet to more meat and dairy products. Firstly, as its amino-acids help neutralise fishy flavours, sake is a sine qua non of a menu with Japanese dishes such as sushi and sashimi, while it goes well too with tempura and tofu. Japanese and non-Japanese sommeliers alike are spreading the word that sake is not just fashionable but a delicious, traditional drink its its own right and that message is spreading beyond the Japanese community and Japanese restaurants. Much of this is premium sake, a far cry from the cheap, mass market stuff, futsuu-shu, that accounts for four in five bottles produced. Ironically perhaps, the fact that premium sake is expensive and considered as much a luxury brand as a premier or grand cru wine works in its favour in style-conscious, monied circles.

There’s still a long way to go though for sake in the west. Up to a point it’s been helped in the UK by traditional Japanese restaurants and the trendier likes of Alan Yau’s Sake No Hana and Marlon Abela’s Kyoto-style Umu. Premium sakes are available in a variety of styles from upmarket grocers such as Selfridges and Harvey Nichols, but they are expensive, difficult for the uninitiated to get a handle on thanks to off-puttingly high prices and back labels in Japanese hieroglyphics. Most supermarkets tend to have a token sake, but it tends to be the basic, entry level stuff that hardly inspires newcomers to trade up. Japanese sake brewers are as disparate a group as French wine growers, but equally they have a common interest in bringing this unique product to the west. Continuing pressure on them to export and market to a western audience is one way at least to ensure that more of that liquid gem of Japanese culture comes our way.

What is Sake?

There are some 1,400 Japanese brewers making sake in Japan, the most traditional areas being Nada and Itami in Hyogo, Fushimi in Kyoto, Ikeda in Osaka, Niigata and Hiroshima. Sake comes in a variety of shapes and sizes, semi-sweet or dry, chilled or warmed, pasteurized and unpasteurised, still or sparkling, everyday and premium.

Over three-quarters of sake is basic futsuu-shu, table sake that is, made with run-of-the-mill rice, often using automated processes and cut with distilled alcohol for economic reasons. Most is sold in cheap tetrapaks as an everyday drink. A higher grade known as honjozo has a limited amount of brewer’s alcohol added. If no extra alcohol is added, and at least 30 per cent of the rice is polished away, the resulting premium sake is known as junmai. At the top of the tree, premium sake made from rice polished down to at least 50 per cent of its original size is known as ginjo and daiginjo.

The extent to which the rice has been ‘polished’, i.e. the outer layers of protein and fat removed and starch left, determines the finesse of sake. The remaining starch is first turned to sugar by obtaining a koji, or rice mould, which is added to rice, yeast, and water, and fermentation then takes place. Sake is normally served in china decanters called tokkuri and drunk from small ceramic, china or porcelain cups, known as ochoko, or larger sized cup, guinomi, and also wooden bowls or glasses.

Terms

Amakuchi – slightly sweet sake.

Atsukan – sake served warm.

Daiginjo –polished to under 50 per cent, light, complex and fragrant.

Futsuu-shu – ordinary sake.

Ginjo – premium sake polished to under 60 per cent.

Honjozo –30 per cent of the rice polished away with a dash of distilled alcohol added.

Junmai – pure rice sake with no added alcohol.

Karakuchi – dry sake.

Nama – unpasteurised sake.

Nigori – cloudy, often sweet, sake.

Reishu – sake served cold.

Yamahai – a ‘wild’ traditional sake style.